Griener Dunnerschdaag (Green Thursday)

According to Pennsylvania Dutch tradition, today is Griener Dunnerschdaag (Green Thursday), a culturally-specific name for Maundy Thursday in the liturgical calendar of the christian church.

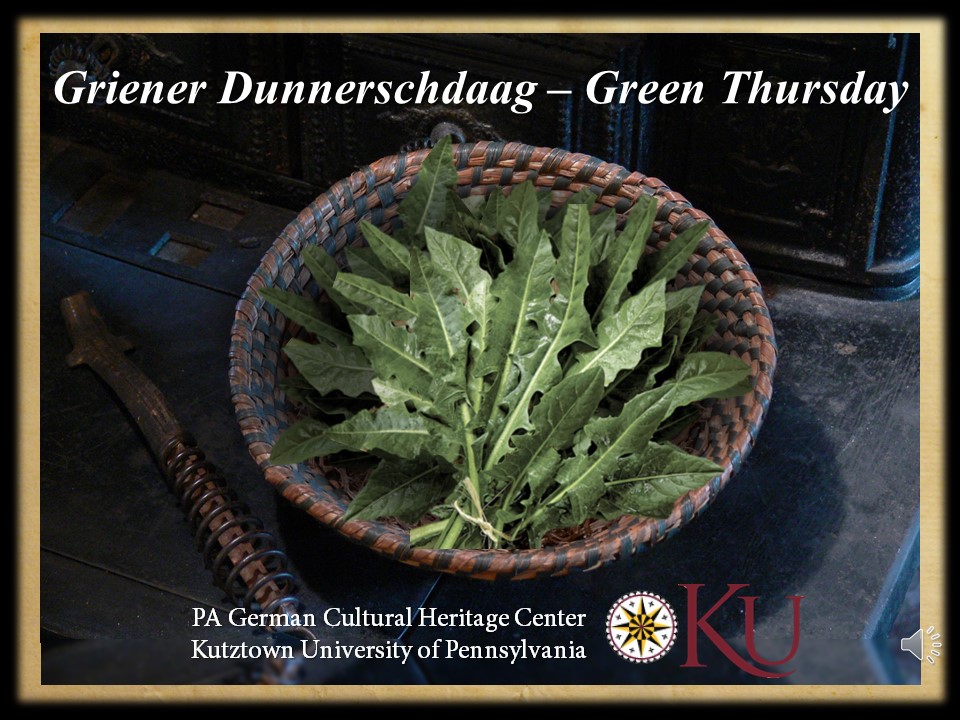

On this particular day as the name implies, it is traditional among the Pennsylvania Dutch to eat something green. For many generations, this was wild greens, and dandelion (Bissebett) was considered a delicacy when young and tender. Other wild greens from the brassica family were also eaten, such as watercress (Schpringegress), chickweed (Hinkeldarrem), and if you were feeling particularly desperate, the morbidly bitter charlock field mustard (Moschdert) and wild lettuce (Millichgraut) would suffice. The bitterness of all of these greens was at least partially dependent on when Holy Week fell on the calendar each year. If it was early in the season, the greens were smaller and more palatable. Once they bloom, the greens become increasingly bitter.

All of these greens were once considered to be medicinal spring tonics for purifying the blood and preparing the body for the transition from the winter cold to the labor-intensive growing season. Families would go out into the fields and meadows with big oak-splint gathering baskets to harvest the greens for a salad served with hot bacon dressing and hardboiled eggs. The coming of spring is celebrated by eating greens across many cultures, yet very few are aware of the origins of this particular tradition.

According to custom, Green Thursday was set aside as a day for fasting, and typically the first of three days in succession, during which no meat was to be eaten, and greens were acceptable fare on days of fasting. Etymology suggests that originally “der grüne Donnerstag” may likely have held a different meaning. Rather than the color green, it was so-named with an old spelling of the word “greinen” (to lament), in keeping with its recommendations for fasting and penance. However, the unusual English word “Maundy” comes from the Latin word for “that which is mandated” – a reference to a new biblical “commandment.”

According to Christian tradition, Christ and his disciples celebrated Passover in Jerusalem. The story relates that Christ washed his disciples’ feet, and told them to “Love one another” as a new commandment. Christ also departed from tradition that evening by blessing the bread and wine as his body and blood, establishing the symbolism of the Eucharist, or the ritual of Holy Communion. This occurred on the very same night that he was betrayed and arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, and the following day he was crucified on Good Friday. The majority of the Pennsylvania Dutch were members of Protestant churches and the observation of Green Thursday was a central part of Holy Week, when services were held in the evening of to remember the Last Supper. Among the Moravian, Anabaptist, and Pietist portions of the Pennsylvania Dutch community, especially among the Brethren, this service incorporated footwashing as part of their annual Love Feast celebration. Footwashing has more recently become widespread among protestants too, when some congregations re-enact the biblical narrative.

As religious observations influence broader trends in secular culture and vise-versa, not all Pennsylvania Dutch people necessarily took such interest in the biblical symbolism of the day. Some simply knew from oral tradition that “Uff Griener Dunnerschdaag sott mer ebbes grienes esse, noh grickt mer ken Fieber, Leis, odder Gretz!” (On Green Thursday, one should eat something green, then one won’t get the fever, lice, or the itch!)

Please Note: An earlier version of this article posted on 04/09/20 incorrectly suggested that Christ and his disciples celebrated the Seder, which is the traditional Jewish Passover meal, during which bitter greens are eaten as part of the meal. In fact, the Jewish celebration of the Seder emerged from rabbinical Judaism long after the time of Christ. Although many Christians are interested in Jewish Passover traditions because of perceived parallels with the gospel narratives, this interest is controversial, and unfortunately misconceptions and cultural appropriations abound during the Christian celebration of Holy Week. We appreciate the constructive suggestions from some of our readers to correct our post, and sincerely apologize for perpetuating a misinterpretation. As a cultural institution, we stand in solidarity with our Jewish friends and neighbors whose vibrant traditions are an important part of the region’s heritage. We hope that those who are interested in learning more about Jewish history and customs will join us in doing so in dialogue with members of the Jewish community.